San Francisco University High School Alumni Association Fireside Chat with Marc Zegans ’79, 10/3/17

Telling Transitions on the Path to a Fulfilled Creative Life: A Conversation between Marianna Stark ’89, UHS director of alumni engagement and giving, and Marc Zegans ’79.

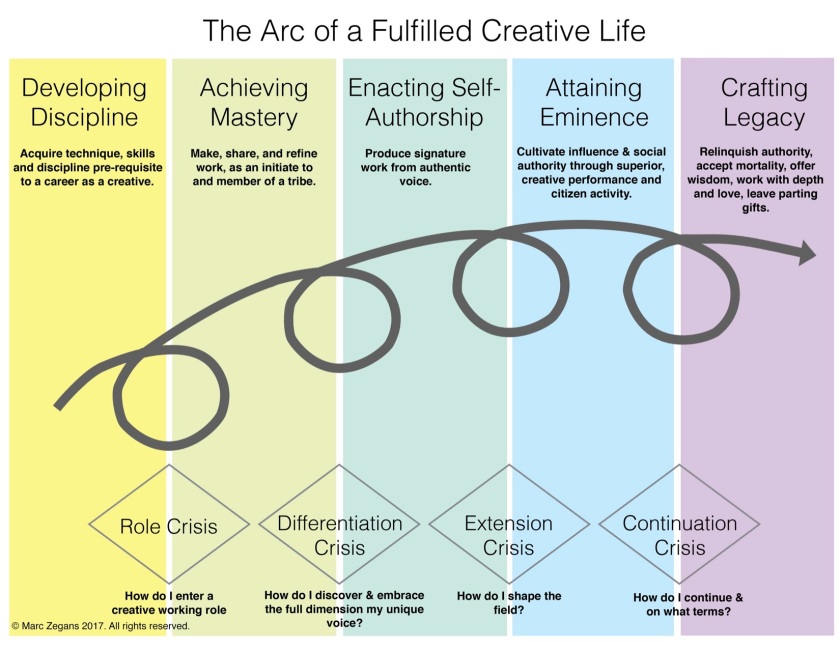

On October 3, 2017, Marc Zegans came to UHS for a Fireside Chat with alumni and parents. He spoke about the transitions we make in our creative lives as we move from high school to college, from college into creative careers, and then in mid-life, when our kids start to leave home. The following conversation highlights topics addressed in the live event.

Marianna: I thought that in our conversation, it might be a great opportunity to explore some questions that grew out of your recent fireside chat at UHS. I’d like to begin with a few questions that are on the minds of folks who are just starting out, and their parents.

First up, a big one, “should I get a BFA? Or just take art classes in college?”

Marc: If you live for your art, and if your practice requires intensive training, then yes, get a BFA. Otherwise, take art classes in college. Pursuing a broader degree will allow you to develop variety and dimension in your thought, expression and critical faculties. This richness will give you a more robust set of problem-solving skills and a richer experience of life as a foundation for your art.

Marianna: For those of our alumni in college and graduates who may be considering a return to school, “Should I get an MFA?”

Marc: Know why you’re considering an MFA and explore whether there are better, less costly alternatives that will meet your needs.

Let’s consider both sides. Here are three particularly good reasons to get an MFA: 1) You want an immersive educational experience; 2) there are significant gaps in your skills, and you learn best in an environment that combines formal instruction with the opportunity to socially engage with peers going through the same experience; 3) you want to teach, and the credential is the fastest, most secure route to an excellent teaching position.

On the other hand, don’t delude yourself about why you’re going, and be sure that the program you enter has a reasonable prospect for meeting your expectations. For example, there are 317 accredited fine arts colleges in the U.S. and 417 masters programs in the visual arts alone. In creative writing the number of MFA programs grew from 156 in 2008 to 244 in 2016. I mention these figures because they tell us two things: 1) there’s money in the MFA for the institutions that offer them, and 2) more and more people are seeking and completing MFA degrees. But, if you’re going for an MFA in the belief that the degree per se will give you a pipeline into the higher echelons of the art, publishing or film worlds, you will find by and large that this is not true.

If you’re admitted to one of the very few feeder institutions, Yale and CalArts in the Visual Arts; Stanford for Documentary Filmmaking; USC, UCLA or NYU for film; Columbia or Iowa for Creative Writing; Yale, Julliard, Carnegie Mellon, NYU or Brown for theater, to name a few examples, their reputations, alumni networks, faculty and quality of instruction will open doors for many, but not for all their graduates. You should know that the marquee value of the institution drops rapidly once you leave the very top end of the list.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t many excellent programs out there, or that they don’t do their best to secure opportunities for their students and graduates. It is to say that if you enroll in such a program, the degree itself will not do much to validate you in the larger art world. You will have to be resourceful in doing that for yourself, and accordingly should attend such programs for other, primarily developmental, reasons.

Marianna: Many of our parents and parents of our recent graduates are thinking, I have a loved one or loved ones at this stage, how can I support them?

Marc: That’s a great question. The first, and often the most difficult, step is to create a sense of openness and possibility in the way you relate to your loved one. This means consciously choosing not to project your anxieties about talent, money, opportunity, how artists are seen in society, the embarrassment of having a kid who’s making work that you don’t understand, or that is subversive or controversial onto your loved one. It means also not projecting often naïve assumptions about what constitutes success, and the best way to achieve it, onto your child. Although, if you really do know how things work in the art world, either because you are an artist, or because you’ve done your research, you can make yourself a useful resource for your loved one. You do this best by inviting dialogue and letting your child come to you, not by delivering unsolicited advice in a judgmental tone.

A second good way to support your children is to realize that your role is to encourage their interest in finding ways to develop their craft and to make meaning through their respective modes of creative expression, and then to explore with your children how at this stage of their lives these ends can be best accomplished.

You should know from that start that the best path for developing a fulfilled life as an artist may not lie in trying to make a living from one’s art, nor may it come from working in an art related field. Wallace Stevens, for instance, was an insurance executive whose work gave him the time and resources to develop his craft as one of the 20th century’s great American poets. Similarly, William Carlos Williams was a doctor, and his work was directly shaped and influenced by his medical training and practice. The brilliant short- story writer Louis Auchincloss spent his career working at a white shoe law firm in New York. Yet, the universal reflexive question of parents with kids thinking about a life as an artist is, “Can you make a living at it?”

So let’s take a moment to honor the concern, but to reframe that question in a more practical way, “Must my child earn a living from his or her art in order thrive creatively?”

Sometimes, because the work demands it, the answer is yes. In these cases, for your loved ones to forge meaningful creative lives, they will have to make a living through by their art. More commonly though, they will have to find ways to finance extended periods of time devoted exclusively to creative activity. By working with your loved one to discover what’s truly necessary for them to thrive and to make work of growing depth and meaning, you’ll be in a position to actively help them, rather than be a source of doubt, insecurity and contradiction.

More than anything our kids want to know that we love them; that we are behind them; that we will stand by them, and that we will grow with them. Beyond, this if there are

practical ways that we can help without meddling or imposing conditions that interfere with their growth and autonomy, we can take great pleasure in doing so. Generously given with good intention, our contributions will be much appreciated.

Marianna: A common question we hear from younger alums is, “I’ve just graduated from college and I want to make art, but I need to get a job. Can I do both?”

Marc: Of course you can do both. It’s a time-honored tradition. Most people starting out in the creative arts have day jobs or side gigs of one kind or another. The real question you want to ask is, “What kind of time and resources do I need to do my best work— really, not in fantasy?” Set aside the time you truly need, at the times of day that best fit your personality, for your creative activity, then ask, “How can I use my remaining time to gather the resources and cultivate the alliances I need to support my work?” Once you start thinking and acting strategically in support of your highest and best self, possibilities will begin to open.

Marianna: This goes back to our earlier topic, but from a different angle, “Can I make a living as an artist?”

Perhaps yes, perhaps no, but what you can do is find a way to consistently produce and share work that holds meaning and interest to you, and you can take practical steps to bring your work to market, find grant support, crowd fund projects and attract resources that make the prospect of earning a living through your art more likely. Meanwhile, you’ll be having fun, producing work and growing in your creative capabilities.

The key thing is not to make your determination to produce work that matters to you contingent on whether the work itself will support you financially. If instead you ask, “How can I create the circumstances in which I can lead a creatively rich and fulfilled life by doing my best work?” then you have a far greater prospect of finding health, happiness and success.

Marianna: Turning from making a living and getting your art made to the question of what to do with it, if I’m starting out, “How can I get my art into the world?”

Marc: You can get your work out there by seeking channels, champions and venues most appropriate to the work itself, and by having the courage to persist until you find such opportunities. It’s easier to persist when we don’t set expectations for what must happen with a given project or body of work, but rather concentrate on who we are meeting, what we are learning and who is receptive to our art. Gratefully accepting and building on what comes builds confidence, expertise, community and robustness.

It’s also helpful to take the long-view. Work sometimes travels slowly into the world, especially meaningful work that isn’t simply a superficial bit of trend jacking. If you stay at it, you may find that your work is discovered and rediscovered as you move along your path. When you begin to show more often, some of the people you meet will become curious about your previous work and other projects. That’s why it’s important to develop and nurture ongoing relationships with fans, collectors and the individuals who make up your audience. As these relationships grow, so will interest in your work.

Most importantly though “ask for what you need!” A very good place to start in learning how is to read performance artist Amanda Palmer’s book, “The Art of Asking: How I

Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help.”

Marianna: Along similar lines, “How do I get signed with a gallery?”

A better question is, “What’s the right gallery for me at this stage of my career? If you explore what sort of gallery representation you truly need, and then begin to research what galleries can give you that kind of representation, and of them, given their mission and history, which would be attracted to your work, you can find a sensible way to engage them.

Note, that there’s an underlying pattern to the way I’m reframing these questions. I’m turning them from hopeful, but anxious expressions of concern, into strategic queries that lend themselves to concrete answers. Good things tend to happen when you are quite specific about what you’re looking for and why. It’s easier to connect with people when there’s genuine shared interest and opportunity, and when you know where that lies.

Marianna: Many artists hopefully wonder, how do I get a museum show.

Marc: A solo show in a museum is normally something that happens either when an artist has become well established or has created tremendous currency in the art scene. Inclusion in museum collections and in curated shows is an important building block in a career that can be put in place quite early. For artists starting out or in mid-career, here are some basic approaches:

- Have a prominent collector who is familiar with your work approach a museum about donating one of their pieces to it’s collection. It’s important that the work the donor is offering is relevant to the museum’s mission and that it is of sufficient quality and interest to pass muster with the acquisition committee.

- Approach a museum directly about donating a piece of work. Take the time to research the collection, the museum’s acquisition policy and to explore the curator’s recent programming, focus and interests.

- Ask the museum if they have a discretionary acquisitions fund, approach a junior curator who has a portfolio that matches your work, present your work and ask if this person might be willing to make the case for an acquisition.

- Seek to be included in round-ups, biennials and other periodic exhibitions in which museums are actively seeking work from emerging artists or from artists whose work fit one or more aesthetic, conceptual or demographic categories (i.e. ground-breaking, mixed- media installations by emerging female Latina artists from the Bay Area.) The more closely the curatorial project matches who you are and what you do, the more reason the curator has to get to know you.

- Propose pop-up, off-site, museum sponsored projects, most likely in collaboration with a junior curator. These projects give the museum an opportunity to engage the community. The timeline for planning is shorter than a major show in their main facilities, and it gives a junior curator a chance to develop skills and build reputation. Such shows are the museum equivalent of a corporate innovation skunk-works, often the most exciting and potent source of new ideas. They bring life to the institution with little downside risk and great upside potential.

- Propose a public program at the museum, especially one keyed to prominent themes in their upcoming exhibition calendar. Possible programs might include a talk and slideshow in their auditorium, a panel discussion, a workshop, a brown bag lunch with patrons and curatorial staff, a conversation with docents, or any relevant activity that gives you an opportunity to share your work in connection with the museum’s broader curatorial agenda.

Good places for beginners to explore this topic in greater depth are Brainard Carey’s books, “Making It in The Art World,” and “Demystifying the Art World.”

Marianna: You talked earlier about not equating success as an artist with the income you derive from your work. What then does modest success during the early stages of a creative career look like?

Marc: Modest early success means that you are actively finding ways to make, share and possibly sell the work that you want to make; that you are mastering the social context in which you make art as part of your creative identity, and that you are committed to a practice of developing the self-mastery needed to thrive in the un- scaffolded context of life outside the art school door. It means, also, that you are building a robust support network and resource base, and that the craft, quality and meaning of your work (on your own terms) is consistently improving. Great success means that you have developed the passion to want to make work for the rest of your life and the determination and adaptive resourcefulness to make this a genuine possibility.

Marianna: Budding artists often ask, “How can I get press? Marc: Take a journalist to lunch.

Marianna: Let’s turn now to parents and mid-career alums, folks who are a bit further down the road in life. I find that they raise these sorts of concerns, “I’ve been making art for a while holding down day jobs. I want more people to see my work, but I don’t have the time. I also don’t want to sell out and make work that fits into current trends to get noticed. What should I do?

Marc: Let’s take the second part first. “I want to more people to see my work, but I don’t want to sell out and pander to the market.” The answer here is simple. Make the work that holds meaning and interest to you. Do the work for which you are passionate and bring it to the highest level you possibly can. Then ask, who might share these interests? Who might have similar passions or find meaning in this work? Where are they located? How do they spend their time? How do they communicate? From whom do they seek advice? Whose opinions influence them?

These people are the universe that defines your potential audience. Now that you know who they are, you can develop a plan to bring your work to them, perhaps directly, or perhaps through a set of astutely chosen intermediaries—presenters, galleries, publishers, curators and the like. Far better to work from your heart and find like-minded souls than to play a game of “I think the market will buy.” The latter, if you are successful, may be lucrative, but it will not be fulfilling. By contrast finding and bonding with your natural audience will be rich with meaning, and it may be equally or more lucrative than the alternative approach because it is grounded in something real. (If you’re interested in thinking this through more systematically, you can find the link to a brief e-book, I’ve written on the topic here, Finding Your Natural Audience, and several interviews on the topic in the press links on the same site.)

Now let’s look at the second concern, “but I don’t have any time.” When people say this, they usually mean, “I have so little time that I don’t think it will make a difference. I can’t possibly succeed with the scant amount of time I do have.”

This is where your calendar becomes your friend. Rather than despairing, figure out how much time you actually have each week and each month to take steps to bring your work to the world. Schedule this time and decide what particular activity you’re going to undertake in each scheduled slot. You can change your mind later and reprogram as you learn more, but if you lay out a basic plan, you’ll discover that you do have time, more than you think, and you’ll discover that by budgeting your time, you’ll start to use it effectively.

Next, recognize that because your time is limited, it may take a while, months or years before you’re able to bring your work to your audience in the way you desire. This isn’t a failure; it’s pragmatic acceptance of what’s possible and having the courage and commitment to persist.

Once you head down the path of making your calendar your friend, you may still feel that you want more time. Many artists do. If that’s the case, then figure out how much time you really need each week to achieve your goals in a timely manner, and when you need this time. Then ask, “What kind of day job, or service can I organize for myself that will give me the time I need, when I need it and still pay the bills?” When artists go through this analysis, they often find that there are things they can do that pay for better on an hourly basis than they had imagined, and that there are all kinds of ways of assembling work that fits their schedule. The key principle is that they have put themselves in charge of their lives and are actively seeking solutions, rather than passively submitting to existing circumstances.

Marianna: One of the topics we discussed at your fireside chat was the urge of many empty nesters, or people in the second half of their careers to turn to more creative pursuits. Many, however, are still grappling with economic concerns. They say, “I don’t feel fulfilled in my job and want to start making art. However, I still need to save for retirement. Can I depend on art sales to supplement my income?”

Marc: Make art because you want to make art. Write books because you want to write books. You can only depend on sales if you generate them, and if you establish a pipeline that will produce regular income. This is possible, but you have to create work of meaning and value, find your audience and build your business. The advantage you

have over younger artists is that you’ve likely mastered a set of life skills, and have developed a degree of discipline that are conducive to these ends.

Marianna: A comment that often comes up when people are thinking about second careers as artists is, “I don’t think the art I make or want to make will ever find a market. How can I be successful in other ways?”

Marc: his is a good question because the bulk of good art that gets made never finds or only finds a minimal market, so thinking about how to be successful in other ways, is a very healthy means of building a creative life in the second half of adulthood. A side benefit of this intentional approach is that good things tend to flow from focusing on the content of creative expression: making and sharing work that holds meaning, entering into conversation with fellow artists and the larger culture, and deepening one’s expressive capabilities through progression in one’s craft. In some cases, this can include emerging markets for one’s work.

###